I am happy that the Supreme Court shot down the assertion that state legislatures can operate free from their own judiciary review under state constitutional authority, or free from the executive branch fulfilling its duties to citizens. As David French tweeted, they “nuked it from orbit.” To lawyers, the law is a hammer and every issue is a nail. In this case, though legally SCOTUS did the right thing, the legal thing missed the point.

Writing in the New York Times, French observed:

The implications are profound. In regard to 2020, the Supreme Court’s decision strips away the foundation of G.O.P. arguments that the election was legally problematic because of state court interventions. Such interventions did not inherently violate the federal Constitution, and the state legislatures did not have extraordinary constitutional autonomy to independently set election rules.

Other, more legally smart and educated people than me, can opine on the correctness of what David wrote. Tellingly, though the Justices ruled 6-3, including some key conservatives: Brett Kavanaugh and Amy Coney Barrett—both Trump appointments—the outcome was not unanimous. I am not qualified to go into the legal justifications of what might be in the dissenting opinion. But the issue here is wider than the legal case at hand, so I will dispense with the legal part quickly.

The SCOTUS case knocks the legs out from any state, with a Republican majority in the legislature and an activist attorney general, from asserting that the legislature can restrain the courts or the executive branch from interfering in election processes in accordance with that state’s constitutional provisions and powers. For example, the Georgia legislature could not overrule a federal judge who tossed out the state’s “at large” method for electing members of the Public Service Commission, as SCOTUS ruled in 2022. The method was determined to be racially discriminatory.

In 2021, Georgia’s legislature passed a new election bill that Gov. Brian Kemp signed, that gives the legislature much more authority, while stripping the state’s secretary of state, also the chief election officer, of many of that position’s previous powers. But in 2020, courts and the Secretary of State Brad Raffensperger both injected new processes and procedures into the election process that the legislature had not approved.

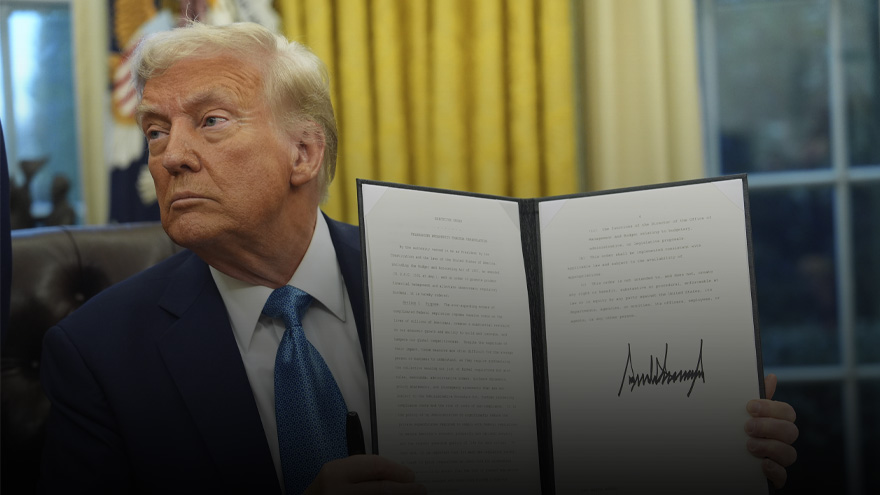

The basis for many of the GOP’s claims, and Donald Trump’s election conspiracies, is that the changes to the 2020 election processes in states like Georgia (along with Pennsylvania, Arizona and Wisconsin) “rigged” the election in favor of Joe Biden, thereby invalidating the results. The evidence does not show that the 2020 election was rigged or invalid due to these changes. So, legally, what SCOTUS ruled is that legislatures cannot go back and say the election was moot because courts and executive branches cannot act independently because the legislature has some higher authority.

Good.

But the problem with the 2020 election was not just that some believed or asserted that legislatures had some insulated, special authority to deal with presidential or federal elections. The problem is that the courts and the executives themselves were blind to the impact their decisions were having on the perceived and actual integrity of election processes and procedures.

For example, in Wisconsin, judges, election officials, and activists battled in court over changes to the absentee ballot process, right up until November 2020. These changes were dealing with COVID-19, as most of the states struggled over mail-in ballots, fearing that citizens would not or could not go to polling places. However, in an effort to ensure everyone could vote, changes involving postmarks and other methods of determining validity were changed, without time for local or state election officials to train staff, volunteers, or design procedures to cope with those changes.

In Georgia, Raffensperger sent absentee ballot applications to every voter in the state in the spring of 2020. The result was a lot of chaos. I still don’t know if my own vote in the primary counted, since Fulton County never sent me an absentee ballot after I requested one, but recorded that I had requested one, so I could not vote in person the normal way. I had to vote “provisional.” Queries of the state voter database show that my vote may not have counted, and my email requests to the Secretary of State’s office have gone unanswered. I know I was not the only one in that primary who had this problem. I showed up to vote at 7:30am, and there were already a dozen names on the provisional list at my precinct.

By November, things had settled down a bit. The new voting system using Dominion’s terminals, printers, and scanners, got its debut in the spring primary, so there was more time by November to train staff. (I still think the system is overly complicated and kludgy but it’s not hacked or controlled by Venezuelan programmers.) The biggest problem was the wave of absentee ballots, which took days to count.

The monkeying with election procedures and processes by courts, the resulting lawsuits, and the intervention—with good intentions—of state election officials to try and cope with COVID and ensure people could vote, injected a lot of uncertainty into the results. Don’t forget, it was Democrats who claimed that U.S. Postmaster General Louis DeJoy was intentionally slowing the mail to prevent absentee ballots from being delivered. That was a thoroughly debunked conspiracy theory. But it did contribute to the loss of trust in the system to operate as intended.

Changes right up to the last minute, all over the country, and especially in swing states, was responsible for the claw-hold of Trump’s stolen election conspiracy. The legal part, where legislators, officials and corrupt lawyers tried to use specious legal means to overturn the election results, flowed from the uncertainty and desire for some to believe the conspiracy. Common sense was difficult to find when there actually were changes.

The judges and officials were blind to the effect they were having on the believability, certainty, and integrity—the perception—of the 2020 election results. That gave Trump a wide lane to claim what he knew would be true: he would be seen as winning on election night, and then within a few days, lose. The results are what they are, and they are correct. But the uncertainty caused people to believe that there is a chance they were not. It would have been better had the judges stayed out of it from the beginning.

SCOTUS closed a legal lane that conspiracists used. But they could not close the road that led to the conspiracy.

Follow Steve on Twitter @stevengberman.

The First TV contributor network is a place for vibrant thought and ideas. Opinions expressed here do not necessarily reflect those of The First or The First TV. We want to foster dialogue, create conversation, and debate ideas. See something you like or don’t like? Reach out to the author or to us at ideas@thefirsttv.com.