A guy from Queens who for years couldn’t decide whether he wanted to be a rock drummer or a lawyer found himself in the most exquisite of circumstances: He got to put a bigger guy from Queens in his place, big-time. Judge Arthur Engoron thinks Donald Trump is a living, breathing fraud, and how much more on-the-nose can it be to try the case alleging exactly that? I imagine it’s beyond understatement to say the judge savored every minute of this case. I mean, Engoron might have “$464,576,230.62” carved into the headstone of his own grave, because it’s his epitaph, right above “I took down the loudmouth fraud and his bratty kids.”

How could this even happen in a country where juries are supposed to render judgements, and punishments are supposed to fit crimes? There wasn’t a human victim in Trump’s case—he was being tried for being himself for 40 years in New York real estate, a business known for being filled with blowhards and self-promoting thieves. Trump was—is—exceptionally good at being a blowhard, not so much a thief. He’s so good that he made the Trump name, sullied as it is, valuable and plastered on buildings from Honolulu to Muscat. The second-tallest building in Chicago is a Trump hotel.

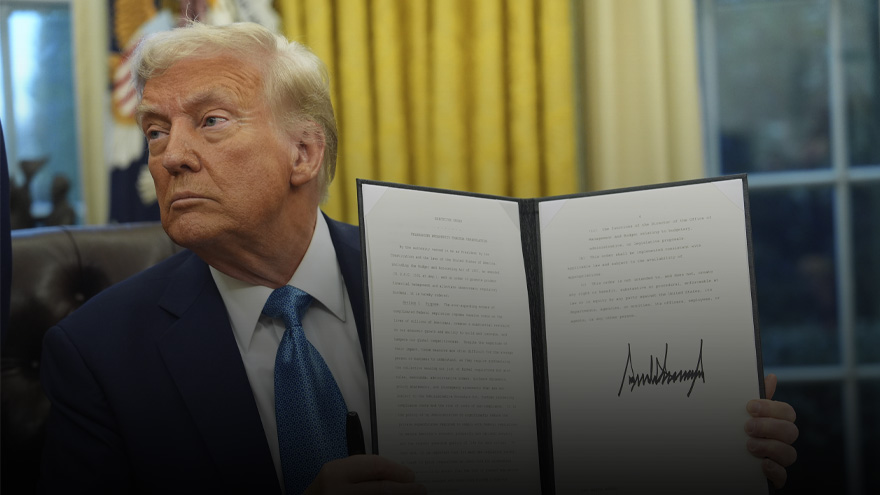

It took a hell of a set of cojones for a judge to take on Trump, basically telling the former president to sit down and shut up. New York Attorney General Letitia James was being political when she went after Trump’s money and business. For Engoron, I’m sure it was personal: he did it the Queens way, wiping the smirk off Trump’s face had to have its own satisfaction.

There was no jury: Just a judge acting with purpose. It wasn’t the “principle” of what happened; it was the “principal” as in the prankster class clown being hauled in front of the person who runs the school and made to answer for his misdeeds. “But nobody was hurt!”

That’s not the point. It was never the point.

There’s a couple of things non-legal people get wrong all the time. I am no lawyer myself but a few good ones have rubbed off on me over the years. One myth is that a jury decides innocence or guilt. The piece of paper says “guilty” or “not guilty,” as a pro-forma way of giving the judge something to read. The judge is really the arbiter of the outcome of the case. This is why people can get bench trials without a jury and why judges can set aside a jury’s verdict (with solid legal reason).

Another myth is that it’s better to get a jury trial than a bench trial. Sometimes it is, sometimes it isn’t. In the case of The People of New York State versus Donald J. Trump et. al., a jury trial was not prescribed by the civil fraud law AG James used to sue him and his posse on behalf of the state. Even so, Judge Engoron noted that “neither side asked for one.”

Juries don’t always help a litigant. In 1986, Trump’s lawsuit against the NFL was decided by a jury, which found in favor of the USFL—they awarded the plaintiffs triple damages on a $1 judgement. Three dollars.

Juries can be capricious. Judges—competent ones anyway—act with purpose.

Engoron not only hit Trump with a yyyyyuge financial penalty, one it will be very difficult for him to pay, or even post a cash bond during appeal; he also ordered Trump and his family stripped of the ability to manage their business in New York, and barred any bank chartered or registered in New York from loaning the Trumps money for three years. The penalty was so destructive that a state appellate judge offered relief—but not much, as Andrew C. McCarthy wrote in National Review:

Nevertheless, Justice Anil C. Singh did give Trump some relief. He agreed to stay enforcement of several aspects of the verdict and judgment rendered by the trial judge, Arthur Engoron. Most consequentially for present purposes, the part that barred Trump from seeking loans has been stayed.

Trump has less than a month to pony up the cash or provide a bond for the full amount, well over $450 million. If he doesn’t the state can start “enforcing” the judgement by carving up the Trump Organization’s properties, leaving creditors cold. And there’s other judgements already in the books, like the ones to E, Jean Carroll, plus the interest, and legal fees which keep mounting.

Though he’s not technically “ruined,” he’s certainly not flush with folding money anymore. But that was the whole point, wasn’t it? To get Trump to the point where he couldn’t afford gas for his aging jet. Or the tiny hope that one day Trump might run out of lawyers to stiff.

I wonder what the case would have looked like had there been a jury? Would the jury have hated Trump as much as Engoron? Would it have mattered? Should one man have the kind of power Engoron had over Trump in a case like this? It bothers me.

What could a guy like Trump do to avoid this kind of ruin at the hands of a judge? Go back 40 years and do something else? Without defending any specific action, how can someone be called on the carpet for a lifetime of doing stuff the only way he knows?

Trump’s isn’t not the only case that bothers me, either.

In the weird, white-shoe world of the Delaware Court of Chancery, billions get decided, quietly, and usually without a whole of fanfare. Well, at least that world weird to the rest of us. As Arnold Schwarzenegger said (and I can’t find the quote now), everything is just another thing once you learn what it is from the people who do it. Judge Kathaleen St. J. McCormick sits and reads these cases all day, questions the litigants lawyers, and then writes 100-plus page rulings on some of the most arcane stuff. Then with the same pen, she cancels Elon Musk.

Literally, McCormick canceled him from the “richest man in the world” when she invalidated his 2018 Tesla compensation plan that is worth $55.8 billion, saying Tesla’s board of directors lacked independence and used a process she called “deeply flawed” to approve the deal.

This wasn’t the first run-in Musk had with Judge McCormick. In October 2022, she called his bluff on the Twitter deal, forcing him to close the purchase he tried to back out of. Even then, she knew the compensation case was brewing, according to the New York Times.

The 43-year-old judge is also expected to preside over another case involving Mr. Musk in November. A Tesla shareholder accused him in a lawsuit of unjustly enriching himself with his compensation package while running the electric vehicle company, which is Mr. Musk’s main source of wealth. The package, which consisted entirely of a stock grant, is now worth around $50 billion based on Tesla’s share price.

If Engoron vs. Trump was the story of two Queens guys, one who drove a cab before law school, then taught drums and piano for four years before deciding to settle in to a law career, against the rich kid whose dad had the only chauffeured Cadillac in the neighborhood, then the story of McCormick vs. Musk is one of a quiet small-town Delaware girl, whose dad was a high school football coach and mom was an English teacher, against a chunky rough kid from South Africa with a brain for games, whose dad is a serial fabulist.

McCormick deals with dealbreakers and gamers all the time. People are always trying to game some system or another; make deals and break them. Musk is no fraud; he is very analytical. His mind is always trying to find the solution to win in any context, whether it’s business or physics. But Musk is also very controlling. His version of a useful board of directors is one that does what he thinks is the right thing. In 2018, there really could be no other decision the Tesla board would have reached. The only cure would be a time machine, and even Musk can’t produce one of those.

In its essence, the suit McCormick decided against Musk was similar to the one Engoron decided against Trump. They were both being tried for being their authentic selves. Neither needed a jury: Trump’s jury was the seventy-odd million voters who elected him president in 2016, many of whom continued to vote for him in 2020, and even now. Musk’s jury was the throng of investors who drove Tesla’s stock into the stratosphere, at its peak valuing the company higher than Toyota, Volkwagen, Daimler, Ford and GM combined.

Certainly, Trump wold not have been sitting in the dock, or owing over $450 million for a fraud case with no injured party, had he not won in 2016. I don’t need to get into Engoron’s head to determine if he really thinks that a better outcome than Trump losing in 2020, brought to near-ruin in 2024, and possibly even prison. Of course he does.

I can’t get into McCormick’s head to know if she thinks it would be a better deal for Tesla shareholders had the company board not approved Musk’s compensation plan in 2018, and the company didn’t become one of the world’s most prolific EV manufacturers, leading an entire industry out of internal combustion engines, while providing the capital base to help fund SpaceX, Starlink, and even (great heaving sigh) X, formerly known as Twitter. Perhaps she doesn’t care—she only sees a man who is, in her logical, fact-pattern thinking, too big for his britches.

Both men were being their authentic selves. And both were taken down by the principal, a single individual armed with the law. The story isn’t over by any means: Trump could end up with a reduced judgement on appeal. He could end up getting the cash. He could end up president again. And Elon Musk will keep gaming; he’s already moved SpaceX’s corporate registration to Texas.

But somewhere in my mind, it bothers me that judges without juries, without victims, without a crying mother or grieving widow, can inflict such huge outcomes on people. It doesn’t really matter if they deserve it or not. It’s the principle—or the principal—of the thing.

Follow Steve on Twitter @stevengberman.

The First TV contributor network is a place for vibrant thought and ideas. Opinions expressed here do not necessarily reflect those of The First or The First TV. We want to foster dialogue, create conversation, and debate ideas. See something you like or don’t like? Reach out to the author or to us at ideas@thefirsttv.com.