There has been a lot of discussion over the past few months about the future of the filibuster. Much of the debate has centered on the rights of the minority and protecting Senate traditions, two topics that also relate to another controversial custom. The filibuster isn’t going anywhere at the moment, but it may be time to consider changing another old tradition. I’m speaking of the gerrymander.

Gerrymandering, of course, is the practice of drawing congressional districts in strange shapes to gain partisan advantage. In many states, gubernatorial and state legislative elections take on outsize importance in census years since the party in power gets to redraw congressional districts and often does so to maximum advantage. This sometimes yields results that are wildly different from the balance of voters.

For example, North Carolina and Maryland are considered to be two of the most heavily gerrymandered states in the Union. In North Carolina, a battleground state, Democrats won the congressional popular vote by about one percent in 2020 but Republicans still won two-thirds of congressional seats. In Maryland, Republicans got 35 percent of the vote but only hold one seat out of 10. As you can see, both parties stand to gain from drawing congressional districts more fairly.

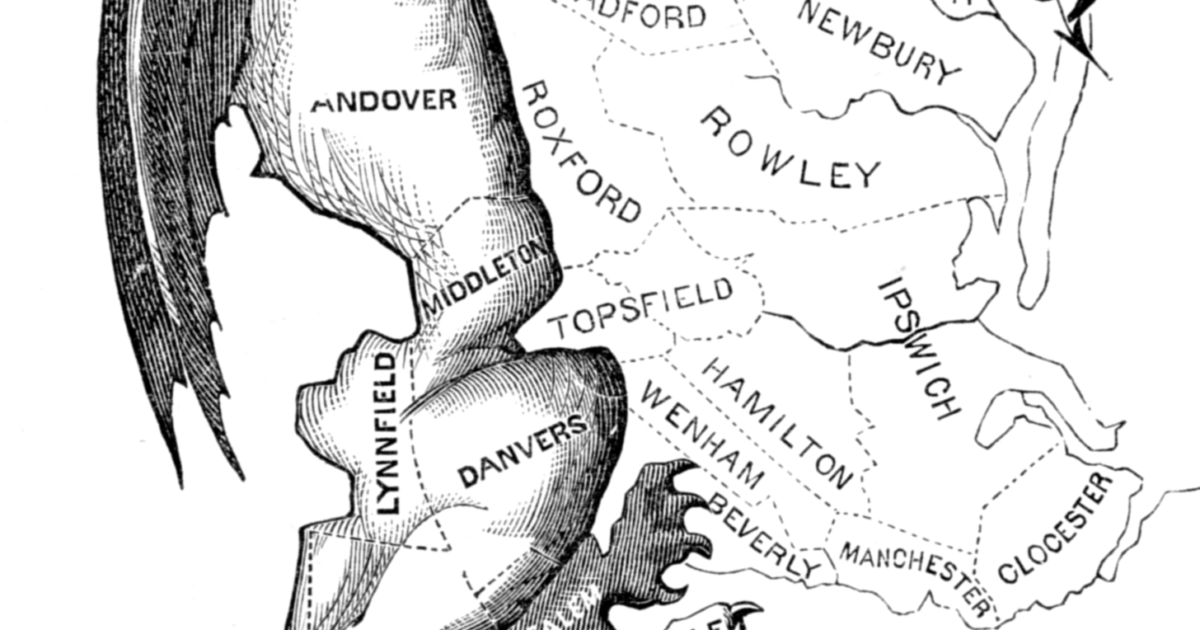

As the cartoon above illustrates, gerrymandering has been around for a long time. The term originated in 1812 with the creation of a district in Massachusetts that was said to resemble a salamander. The result became known as the “gerrymander” after Eldridge Gerry, the governor of Massachusetts at the time. (Incidentally, the word is pronounced with a hard “g” as in “gruesome.”)

The basic procedure is that when a party controls the levers of redistricting in a state after the census, the district lines are redrawn to maximize the home team’s congressional majority. A few of the districts are drawn to isolate the minority party’s voters and dilute the opposition vote while most are designed to create safe seats for the majority. In some cases, districts are drawn to guarantee the election of minority politicians, which also has the effect of thinning the minority vote in neighboring districts.

Another effect of gerrymandering is to empower the fringes of both parties. When a district is safe for one party, the “real” election is the primary. The partisan voters who select their party’s nominee are, for all intents and purposes, electing the congressman since the general election is a formality in many cases. Safe partisan districts are how people like Alexandra Ocasio Cortez and Marjorie Taylor Greene get elected and often stay in office for decades. The Fulcrum has a graphic list of America’s worst examples of gerrymandering.

One of the answers to the problem of radicalism in both parties may be to make districts more competitive. If partisans can’t be anointed by primary voters and must compete for the votes of moderates and independents – and maybe even some voters from the opposite party – it should have a moderating influence on both parties as well as Congress. If the majority party in states like North Carolina and Maryland want to keep their majorities, they would need to do better at reaching out to other voters, not just playing to their base.

Under our current system, many congressmen are rewarded for extreme behavior that panders to the partisan base. And the problem applies to both sides. Republicans may love to hate and ridicule AOC for her gaffes and out-of-touch comments but North Carolina’s Madison Cawthorn, who admitted in an email, “I have built my staff around comms rather than legislation,” is an even less serious legislator than the New York Democrat.

Despite their flaws, both Cawthorn and AOC won their races by double-digit margins. Cawthorn won by 12 points and AOC by 44 points. For her part, QAnon adherent Marjorie Taylor Greene won her race in Georgia by a staggering 49 points. All of these people desperately need competitive challengers.

Gerrymandering is hurting the country, but it is not unconstitutional. The Supreme Court has upheld gerrymandering in numerous cases, but it has limited the practice. From time to time, state courts have gotten involved as well. In recent years, gerrymandered congressional districts have been thrown out by courts in North Carolina and Pennsylvania, nevertheless, it would be inappropriate for the Supreme Court to suddenly rule gerrymandering a constitutional violation and overturn 200 years of precedent.

A better solution is to pass laws that take redistricting out of the hands of the parties through legislation. A handful of states from both sides of the political spectrum have established nonpartisan commissions to draw district lines. Most redistricting is still controlled by state legislatures, however, because the parties don’t like to give up power.

Unlike congressional term limits, which would require an amendment to the Constitution, redistricting reform can be accomplished at the state level by legislators. Some states even provide for popular referendums that enable voters to propose the changes themselves.

Partisan redistricting may be constitutional, but I’m pretty sure that gerrymandering isn’t what the Framers had in mind, and sometimes courts agree, calling particularly one-sided maps a violation of equal protection. Gerrymandering may be an old American tradition, but it is one that needs to be retired.

Follow David Thornton on Twitter (@captainkudzu) and Facebook

The First TV contributor network is a place for vibrant thought and ideas. Opinions expressed here do not necessarily reflect those of The First or The First TV. We want to foster dialogue, create conversation, and debate ideas. See something you like or don’t like? Reach out to the author or to us at ideas@thefirsttv.com.