In two days, Christians around the world celebrate the anniversary of God’s birth into the world as a human child. I don’t think we really comprehend the enormity of that event.

Christians, including me, get wrapped up in our lives. We “do” Christmas, plans, meals, families, the uncertainty of this world, and of course, gifts, and then we’re pulled to the manger in Bethlehem, where a baby was born to two nobodies, and witnessed by farm animals, shepherds, and the heavenly host of angels. It’s all very disconnected and ritualistic. It’s even difficult, apart from reading the Bible, studying ancient historical records, and by simple faith, to believe that something like this really happened.

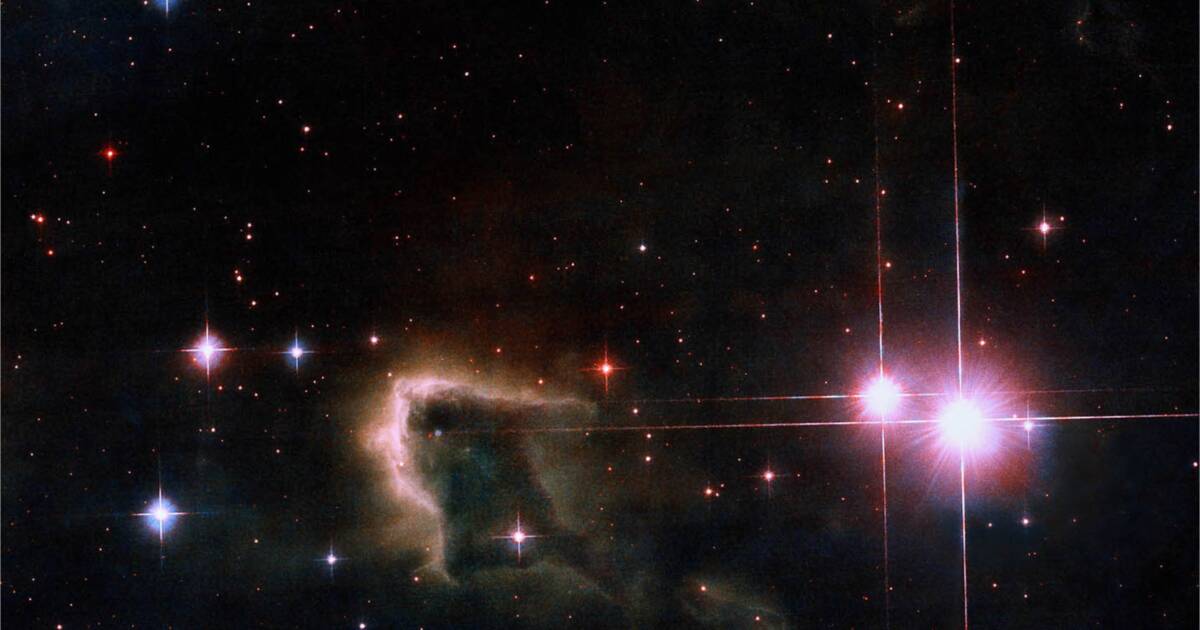

But consider who God is, objectively. God is the creator of being, of matter, of the universe, ruled by immutable laws, mathematical perfection, of energy, waves, particles, fields, dimensions, and time. The being who brought everything into existence from nothing has to be greater than the things he created. For those things to persist for billions of years, God has to be beyond perfect—God is infinite.

For in him all things were created: things in heaven and on earth, visible and invisible, whether thrones or powers or rulers or authorities; all things have been created through him and for him. —Colossians 1:16

We humans understand more of the universe than any other creature (barring advanced aliens). We understand math and the relationships of certain constants, and from those relationships, we’ve built models of how things work. Yet, we can’t comprehend that 𝛑 (Pi) is an irrational number, with an infinite number of digits; it’s fuzzy in that we can’t describe it except to express the symbol. But without 𝛑, we can’t describe a circle, which is one of the basic concepts of geometry, algebra, and trigonometry. Without e (Euler’s number), we can’t derive natural logarithms, or describe complex financial relationships, statistics, or normal distributions. Euler’s number is another irrational number. We can only express it in symbols.

God is the author, and therefore greater, than the symbols we use to describe our universe. Every hypothesis, every experiment man has ever devised to test our theories and moments of inspiration, is a continuation of the search for the divine nature. We struggle to know, and to solve ages-long mysteries; yet Fibonacci, in the 12th and 13th century, found that the segments of a Nautilus shell follows a strict mathematical sequence, as elegant and beautiful as it is immutable. Fibonacci’s sequence appears in the shape of spiral galaxies, and in sunflowers. It just is.

One day, years ago, I was at a Christian fellowship weekend at a campground in the woods. I was walking at night along a dark road, and looked up at the sky filled with stars. I found myself filled with wonder, overwhelmed at the enormity of the universe seen from my tiny eyes on a little planet hurtling around a nondescript star.

I can count the number of times God has spoken to me on the fingers of one hand, and have fingers left over. I am no prophet Elijah. You may even question that God speaks to people, and that’s fine. Theology is a human invention. But that night, I asked God, in the most childlike manner, speaking out loud, a single question: “why?”

When I asked God “why?” that question carried a whole lot of meaning in one little word. Why are we in a universe so large that it’s physically impossible to explore it all, even if we had immortal lives to do it? Why do you say you love us so much, but have given us such unsolvable mysteries? Why, God, did you make something so unbelievably large and unplumbable in depth, for us, these weak, tiny little humans, whose lives flourish and wither like flowers in a field?

And God answered. “I thought you’d like it.”

I do.

It is that simple? But for God, nothing is impossible. The God who brought stars, quasars, black holes, and light into existence from nothing, can do whatever he wants. Two thousand years ago, God’s plan to redeem the human race from its corruption reached an inflection point, a convergence of cosmic significance that placed a star in the sky, which had been seeded with the birth of the universe, and a baby in Mary’s womb, which had been seeded by God himself. God had spoken to men and women throughout the history of written word, and then went silent for 400 years.

In a quiet stable, under that star, God’s own seed, the person of the Son, Jesus, the Messiah, came into the world as a baby. Jesus would tell us the purpose of mankind, in service to God and to the world. He would tell us not to waste our time in pointless argument, but to appreciate and be thankful for the overabundance God the Father has provided. He would preach the most famous sermon in history, the Sermon on the Mount, giving us the beatitudes. He would tell us that he must go and suffer, and that he will return.

Then God on earth gave up his life, the force that searches for divine order and that relentlessly pursues the immortal and the inconceivable greatness of God, into the Father’s hands, bending like a reed to the power of man’s politics and conquest, but not breaking. Jesus faced temptation, and Satan the enemy of our souls, and defeated them. He returned with a glorious, incorruptible life that is our inheritance in Him.

Why would God do all of that for me, for you, for mankind? Why would he redeem all of history, and every moment of our fleeting lives, so we can spend eternity knowing the bounds of His infinite being?

“I thought you’d like it,” says the Father. He gives us everything in such a casual love, but such a pure, and holy, unassuming love. God loves us for who we are, and asks for nothing more than we enjoy all He has given us.

Follow Steve on Twitter @stevengberman.

The First TV contributor network is a place for vibrant thought and ideas. Opinions expressed here do not necessarily reflect those of The First or The First TV. We want to foster dialogue, create conversation, and debate ideas. See something you like or don’t like? Reach out to the author or to us at ideas@thefirsttv.com.