In 1959, Rev. Kyle Haselden, wrote “The Racial Problem in Christian Perspective,” which took five years for Harper to publish, in 1964. Haselden pastored an all-Black church in Charleston, West Virginia. When the book hit, the New York Times, published Haselden’s essay, “11 A.M. Sunday Is Our Most Segregated Hour.” It’s a marvelous piece of writing, that has stood for 58 years without losing relevance.

Nevertheless, not the extremists but the great, white midstream America—i.e., Christian America—produces and preserves the racial chasm in American society. The indifference, inflexibility and inactivity of the religious community—the clergy and the laity—guarantee a worsening racial conflict.

Only within the last year has the “great, white midstream America” problem of the church been seriously addressed by the biggest white evangelical denomination, the Southern Baptist Convention. The cost of ignoring this festering wound, in disciples and—I daresay—in souls, has been catastrophic.

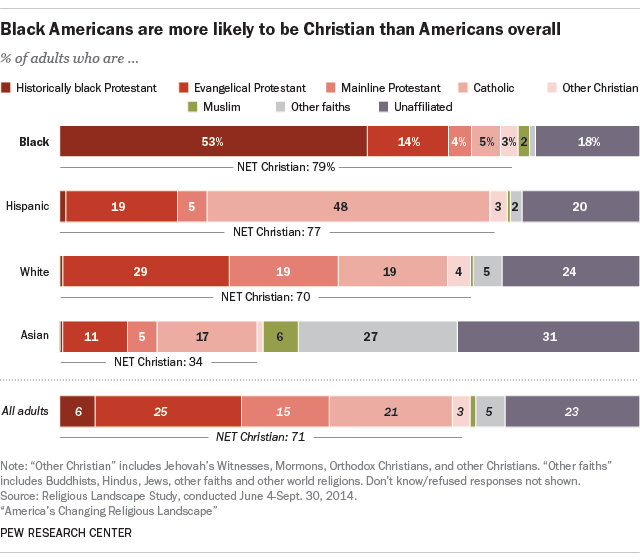

Southern Baptists lost 288,000 members in 2019, nearly 2 million less than the 16.3 million the denomination had in 2016. Many Christians blamed secularization for the shift, but that doesn’t really tell the story. According to a Pew study, 2014 church attendance among Blacks was 13 percent higher than whites, and higher than Asian-Americans, Latinos or others.

In 2018, Pew found that 79 percent of Black Americans identify as Christian, including 70 percent of whites, including Catholics. About 48 percent of white Americans identify as Protestant, while 53 percent of Black adults told researchers they are part of a historically Black Protestant tradition, though this number includes those who say they are part of a broader group that traditionally had a sizable number of historically Black denominations.

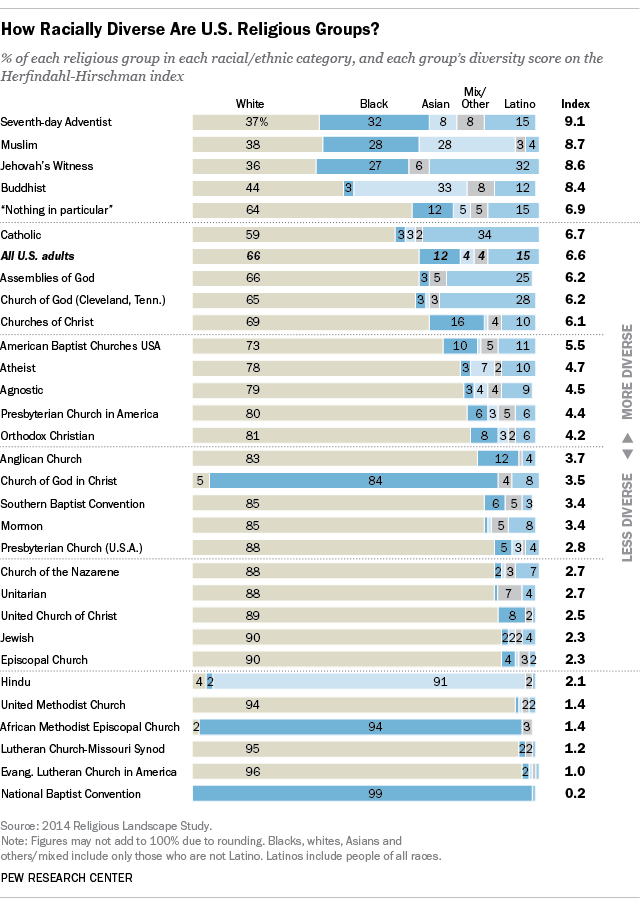

Pew’s breakdown of denominations by race shows a stark segregation that persists since Haselden penned his NYT essay. The most integrated religious groups are not mainline or evangelical, or necessarily even Christian. The “whitest” groups are not necessarily the “least Black” either.

For instance, Catholics are only 3 percent Black, but 34 percent Latino (as you might expect). The United Methodist Church’s share of Blacks is almost immeasurably small, closely followed by the Mormons (LDS), and the Lutheran Church-Missouri Synod. The historically Black church denominations are, predictably, almost entirely Black, though 2 percent of the African Methodist Episcopal Church’s members are white, along with 5 percent of the Church of God in Christ.

It seems that little has changed since 1959 in the religious world, though the secular world has progressed a great deal. Indeed, Haselden’s biggest problem with then-President Lyndon B. Johnson’s call to religious leaders to help solve racial equality was that the church itself was not the source of the problem.

IF, in the President’s words, it is the mandate of America’s religious community to reawaken the conscience of the land, who will reawaken the conscience of the religious community? The President’s second false assumption identified the clergy as the religious community and implied that the clergy can summon the will and the energies of Christian people to a solution of the racial problem.

We must distinguish between the clergy—a minority of which is now committed to and active in the struggle for racial justice—and the church, the religious community, the faithful—a still smaller minority of which is committed to and active in the struggle for racial justice. Both of these minorities working together have not been able thus far to swing the great bulk of religious America into the crusade for an integrated America free of racial discrimination.

Since the 60s, there has been progress in both the church and the secular world, but the gains have almost exclusively been witnessed in the secular world. In 2020, NPR’s “All Things Considered” noted that multiracial congregations don’t always bridge racial problems outside the church—or even inside.

“Integrated churches are tough things,” says Keith Moore, a Black pastor in Montgomery, Ala., who works closely with local white pastors. “When you see both African Americans and Caucasian Americans [in a church], it’s more than likely to have a Caucasian pastor,” he says. “I think it’s sometimes more difficult for whites to look at a Black pastor and see him as their authority. That’s a tough call for many.”

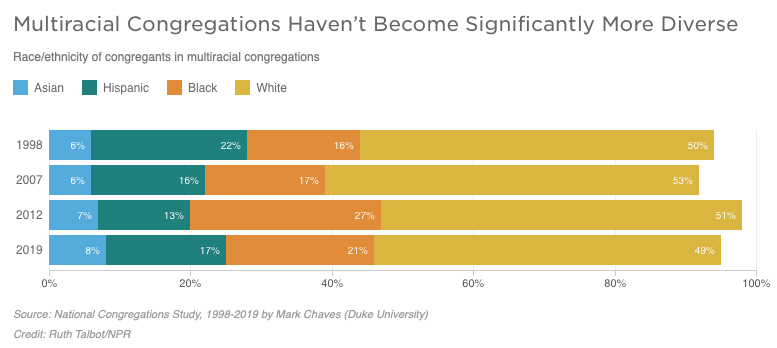

Though the number of multiracial congregations has increased from just 6 percent in 1998 to 16 percent in 2019, the racial makeup of these churches has not changed significantly.

I think this actually makes sense, and isn’t necessarily reflective of the success of these multiracial churches. If the congregants at a church more-or-less accurately represent the racial demographics of its community, then the church is likely about as good as it gets at bridging racial divides. However, the fact that mostly white pastors, and churches with white congregations becoming multiracial might have some meaning.

“All the growth [in multiracial churches] has been people of color moving into white churches,” Emerson says. “We have seen zero change in the percentage of whites moving into churches of color.” Once a multiracial church becomes less than 50% white, Emerson says, the white members leave. Such findings have left Emerson discouraged.

Again, these figures could be reflective of other factors outside the church. Is the community itself becoming majority Black, and therefore community factors—racially motivated, probably—have the whites moving out?

Another question is why historically Black churches are less inviting of non-Black members, or is it that Black pastored-churches with a Black majority aren’t appealing to whites? In our racial hair trigger secular culture, many see the purpose of the church is to become an “equity” player, such that white power structures, like pastorates, are subject to the same scrutiny as those in, say, the NFL.

In Columbus, Ohio, Korie Little Edwards found a similar pattern in her own research. After her personal interest led her to join a multiracial church, her subsequent study left her skeptical that such churches were making the difference in promoting equality that she had hoped to see.

“I came to a point where I realized that, you know, these multiracial churches, just because they’re multiracial, doesn’t mean they have somehow escaped white supremacy,” she says. “Being diverse doesn’t mean that white people are not going to still be in charge and run things.”

There may also be a “ceiling” for Black participation in white-pastored multiracial churches. I’ve personally heard stories of Black congregants questioned by their families and friends why they’d go to a church pastored by a white man. Some Black church members in these congregations decide that in order for a congregation to truly oppose what they consider a white supremacy power structure (white-pastored multiracial churches), the congregation should cede significant roles and oversight to Black members, regardless of credentials and experience.

And of course, there are still plenty of churches planted in places steeped in old fashioned racism, both white towards Blacks, and some in the other direction.

We sort ourselves

Any time humans gather together in groups, there’s a lot of self-sorting going on. I’m going to state something obvious I cribbed from my pastor. People are simply more comfortable being around people who look and think like them. When someone new walks into a church, they unconsciously scan the room for someone who looks like them. This happens when a family dressed to the nines walks into a relaxed coffee-shop worship jam, or when a lone white guy walks into a church filled with brown-skinned people.

I’ve had that experience myself. Back when I lived in central Georgia, I visited a church in Cobb County while I was doing some work up here. I was the only white person I saw. They treated me royally. In fact, it was one of those churches that asks visitors to stand (!) while the congregation gathers around them and sings (!!). For someone like me, who suffers crowd anxiety, I was praying for the floor to open up and suck me down. But I realize the gesture was made in genuine friendship. I need only point to the Wednesday night Bible study in Charleston where a loving group of souls who happened to be Black treated Dylann Roof with kindness and respect, and he repaid them with their own blood. If there is anything more Christlike and powerful in this evil world, I am not aware of it.

When people new to a town select a church (or “shop” for one because they don’t like the one they attend, which I find somewhat repellent), they look for people they might get along with, and unfortunately, our brains tend to be wired to look first with our eyes.

These days, with real estate prices soaring, and the Great Resignation in full bloom, more people than ever are not only looking for new churches, but they’re moving to places they feel more at ease with, politically and socially. NPR put it this way: “fleeing to place where political views match their own.” I’m not sure that politics is always the primary axis to measure, but it’s certainly the easiest.

After many paragraphs spent cherry-picking a few Facebook groups of conservatives moving out of California for Texas, the writer finally admits another obvious fact:

It’s actually been happening for some time.

Residents have been fleeing states like California with high taxes, expensive real estate and school mask mandates and heading to conservative strongholds like Idaho, Tennessee and Texas.

It’s not just mask mandates, though that could have been the last straw for many, though I think that’s a simplistic analysis.

My own observations go back decades. Massachusetts had an exemption on state income tax for airline pilots whose “base” airport was outside the state, and didn’t live in the state either. I don’t think they have it now, but back then, airline pilots flocked to southern New Hampshire, which has no income tax. They commuted to Boston’s Logan Airport, and flew wherever they were needed for their trips. It only made sense and it had nothing to do with the politics of the pilots.

Libertarians (small “l” and party adherents alike) have flocked to the Granite State as part of an organized “Free State Project” for years. It has brought thousands and their effect on the state’s politics is at times significant, as my brother Jay has aptly chronicled.

It’s no different with churches, and why should it be? When a Black majority church offers to hire a white pastor, the pastor might question why a church where 92 percent of the congregation is Black, with a deacon board two-thirds Black majority wants to hire a pale guy. The correct answer would be that they want God’s will more than the color of the pastor’s skin. But inevitably, it can lead to conflict, because people are imperfect and flawed.

There is no guarantee that hiring a white pastor at a Black church, or hiring a Black pastor at a white church is going to make that church color-blind, or immune to societal race issues. Sometimes, it even exacerbates them.

Politics of race and religion

The interlaced nature of our religious lives and our politics in America has been long documented, going back to Alexis de Tocqueville’s “Democracy in America.” The Puritans and the Quakers, the Anabaptists and the Wesleys in Georgia all figured quite large in the political landscape of early America. Abolition and slavery both had their church adherents, who were willing to spill each other’s blood to support their own views. Both claimed God on their side, though we do objectively know that Scripture abhors one man being another’s property.

On issues like temperance, eugenics, Malthusianism, abortion, civil rights, immigration and free speech, the American church has been firmly on both sides. Catholics in particular were considered to be dangerous in great numbers, and legislation like the Blaine amendment passed by some states was designed to keep their teachings out of schools. The revived KKK supported such legislation in Oregon, now a bastion of unreligious sentiment.

David French recently penned a piece telling us to watch out for some churches so steeped in conspiratorial suspicion that they are fomenting political violence. He cited some church invitations to former Trump national security adviser Gen. Michael Flynn.

Intrigued by the Dream City Church reference in Draper’s article, I went to the ReAwaken America tour pageto see where Flynn was headed next. The first thing you notice is that the tour is sponsored by Charisma News, a charismatic Christian outlet. The next thing you should notice is the list of upcoming venues: Trinity Gospel Temple in Ohio, Awaken Church in California, The River Church in Oregon, and Burnsview Baptist Church in South Carolina.

I have a few problems with David’s logic here. Let me first say that I greatly respect David. He has served in the same denomination I currently attend (Assemblies of God, which I have attended nearly exclusively since I became a Christian in 1999), as an interim youth pastor. David knows Pentecostal Christian doctrine from the inside out, and his a good grasp of many of the people, and the hearts of the leaders, that I also greatly respect. Plus, David is very likely to be the smartest person in any room where he stands, while I’m just as likely to to be the least smart.

I visited the same ReAwaken America tour page. The venues, as David noted, are almost exclusively churches. Most of them are Pentecostal churches of various credentials and fellowships (or independent). But just because a conference rents the space from a church doesn’t mean the church itself is sponsoring the event. There is a difference between holding a conference sponsored by Charisma News, a publication run by Stephen Strang, and inviting Donald Trump to a Sunday morning church service in Dallas.

While I don’t agree with Chrisma’s political views, I can see how many churches, hurting from the COVID-19 shutdowns and loss of revenue, would take the money. The churches aren’t setting the speaker list; they just provide the venue. If David is making the guilt by association argument that churches should deny a place to the ReAwaken America tour because it politically aligns too much with what many of their own congregants believe, then he should with the same gusto go after some of the charlatans and spreaders of bad doctrine that litter pulpits all over America, preaching prosperity Gospel messages while being sure to get that special offering.

Arguing that Pentecostal and rural white churches are spreading politically violent messages because they host a conference or have congregations made up of a large segment of Trump voters is akin to the wet sidewalk causing rain argument. Ask any pastor what happens, aside from churches where the denomination appoints the pastor, when the pulpit preaches something diametrically opposed to the congregation’s political or doctrinal beliefs.

This principle works in more than one dimension. I know of hardline Baptist churches where any hint of the gifts of the Holy Spirit in operation was considered “wild fire” and the pastor experienced the baptism of the Holy Spirit. The pastor didn’t last very long. I know of only one occasion where a Baptist church merged with an Assemblies of God church and the majority of the Baptists joined. I’ve personally been asked to leave one Georgia Southern Baptist Convention annual meeting for running a booth to ask people to volunteer for a (now late) Steve Hill revival (yes, I had advance permission to be there doing exactly what I was doing).

It’s far more likely that the politics of the places where Strang Communications and its Charisma empire chose to host their money-making conferences match the budget and needs of the speakers and backers, than they are in league with the churches that hosted the conference. Who knows, maybe some of the larger churches in the area said “no” and the organizers kept going down the list until they got a “yes.”

French paints a lily-white, head-in-the-sand picture.

The sin of omission is the deafening silence from so many Christian leaders about the threat to the church and the nation from the far right. Convinced by threat-inflation of the danger from the left, and desperate for the unity that is perceived as necessary to confront existential risks, the last thing they want to do is to divide the right. Indeed, they scorn those public voices who dare “punch right.”

Moreover, if Christians know anything about the far right, they know it’s vicious. Silence is the safe course. For all the (legitimate) talk of cancel culture from the left, many Christians self-censor out of fear of the right. They know Michael Flynn is dangerous, but saying so out loud carries a cost. So they remain silent. They stay in their anti-left lane.

The problem is, his picture is very distorted because he’s only seeing through the lens of the fringes. Kyle Haselden had a much more accurate and balanced view, which has endured the years and issues that followed.

The Biblical view

Ideally, the Body of Christ, and the Church, biblically His Bride, is not a racial proposition. In the synoptic Gospels, Simon of Cyrene carried Jesus’ cross through the streets on the way to His crucifixion. The Romans ordered Simon to carry the cross, most probably to ensure that Jesus did not collapse and die before he was nailed to it, as the execution order did not allow the condemned to die before the sentence was completed. One thing historians agree on is that Simon was of African descent, and probably dark-skinned. Simon was Black.

In God’s good and perfect plan, a Black man was chosen to carry the burden for the Son of God in His hour of passion. We know from the Gospels that everything significant during Jesus’ life was done in fulfillment of Scripture and prophecy. We know that specifically, every action that happened between the time Jesus entered Jerusalem for the last time, until He gave up His spirit on the cross was on a timeline and according to God’s plan from the beginning of time. It was no accident that Simon carried Jesus’ cross.

In Acts 2, while the disciples were in the upper room, they received the Holy Spirit and spoke in other tongues. This was no manifestation of a “heavenly language.” The disciples sudden ability to speak was documented:

6 When they heard this sound, a crowd came together in bewilderment, because each one heard their own language being spoken. 7 Utterly amazed, they asked: “Aren’t all these who are speaking Galileans? 8 Then how is it that each of us hears them in our native language? 9 Parthians, Medes and Elamites; residents of Mesopotamia, Judea and Cappadocia, Pontus and Asia, 10 Phrygia and Pamphylia, Egypt and the parts of Libya near Cyrene; visitors from Rome 11 (both Jews and converts to Judaism); Cretans and Arabs—we hear them declaring the wonders of God in our own tongues!” 12 Amazed and perplexed, they asked one another, “What does this mean?”

In the crowd were Libyans, Egyptians, Arabs, Cretins, Medes (Persians), and Arabs. Blacks, whites, browns, swarthy Greeks and Italians, among others. They all heard the Gospel when Peter spoke, and thousands of them came to faith in Jesus Christ. There was no mention that this gift of salvation was only for white people, or any one race. There was no mention of a white church, a Black church, or a Roman church. It’s all Christ’s church.

In Acts 10, Peter was given a vision of a large sheet being let down from Heaven containing all manner of animals, reptiles and birds, many of which were against the Kosher laws of the Jews. Peter saw this vision three times, and then visited Cornelius, who had been given a vision of an angel instructing him to send for Peter.

Peter shared the Gospel with Cornelius, a god-fearing man, and his household.

44 While Peter was still speaking these words, the Holy Spirit came on all who heard the message. 45 The circumcised believers who had come with Peter were astonished that the gift of the Holy Spirit had been poured out even on Gentiles. 46 For they heard them speaking in tongues and praising God.

Both Jew and Gentile, white, Black, and all races, Roman citizen or slave, were and are today equal in God’s eyes. The congregations formed under the early church were likely very strongly representative of the populations where the church was located. But they were also very much open to anyone. Where such distinctions were made, the Apostles rebuked the leaders.

James admonished church leaders not to give any special place to the rich or privileged.

8 If you really keep the royal law found in Scripture, “Love your neighbor as yourself,” you are doing right. 9 But if you show favoritism, you sin and are convicted by the law as lawbreakers. 10 For whoever keeps the whole law and yet stumbles at just one point is guilty of breaking all of it. 11 For he who said, “You shall not commit adultery,” also said, “You shall not murder.” If you do not commit adultery but do commit murder, you have become a lawbreaker.

The Biblical view is clear: a white pastor can lead a Black congregation, and a Black pastor can lead a white congregation. Such distinctions do not exist in spiritual terms, because God sees our hearts with perfect vision. The heart that has been sanctified is not swayed by the color of skin or the ancestry of a fellow believer, or the economic position of a person in need of the Gospel.

Yet we are imperfect and subject to the pressures of life in America, along with our history. The Southern Baptist Convention appointed a Black pastor as head of its executive committee, the first time this has ever happened. Can a white church respect and obey a Black leader?

Can churches aligned with other denominations and Trumpian politics respect and obey a secular government dominated by liberal thought? Can the church overcome the fact that 11 a.m. is still the most segregated hour in America?

I think the answer is that when Christians don’t overcome it, then the church loses souls. Without the anointing and power of God, the church can do nothing. We are accountable for “every idle word” we speak, or every conference we host that doesn’t glorify Christ (even if the theme of the conference is literally to “glorify Christ”). God is not a fool and will not be mocked. When churches mock God, maybe those who attend for their own reasons are fine with it—they have their reward. But those who first walk in the door, or the children of those leaders who participated in the mocking, turn right around and head out to the unchurched world.

The decline in American evangelical churches—especially the segregated variety—might be doom for unsanctified hearts, but it is also proof of God’s superintending love. He will curse the unfruitful and it will die.

Churches that preach the Gospel without regard to race or ancestry, with a genuine heart of love, will grow. I am proud—yes, that word—to attend such a church in Atlanta. What we are now seeing in America is not cause for fear, it’s cause for faith in the Lord to work His threshing fork and do away with that which doesn’t bear fruit.

Any work that we do to socially engineer the skin color, economic background, or political and cultural orientation of a church’s laity or clergy is already doomed to fail. God knew what happens when people self-sort and decide to insulate themselves. It’s right it Genesis chapter 11.

5 But the Lord came down to see the city and the tower the people were building.6 The Lord said, “If as one people speaking the same language they have begun to do this, then nothing they plan to do will be impossible for them. 7 Come, let us go down and confuse their language so they will not understand each other.”

When God said “nothing they plan to do,” He knew that the hearts of unredeemed men and women are evil and self-serving. There would be no evil beyond our grasp. History has proven this out again and again. God meant for us to be diverse, and to serve Him first, and through Him, one another. God meant for us to celebrate diversity, not mandate uniformity. The only place where we will have perfect unity is Heaven, and please note that there’s not a different Heaven for Baptists, Catholics and Pentecostals, never mind for Black, white, Asian or Hispanic. If you think that there is, then you might consider your eternal destination more seriously.

Racism and obsessive nationalism, power politics of racial identity, and love of money do not bear fruit. I, for one am glad to see them die.

Follow Steve on Twitter @stevengberman.

The First TV contributor network is a place for vibrant thought and ideas. Opinions expressed here do not necessarily reflect those of The First or The First TV. We want to foster dialogue, create conversation, and debate ideas. See something you like or don’t like? Reach out to the author or to us at ideas@thefirsttv.com.